While participating in this year’s Aspen Critical Issues and Risk Forum, I had the opportunity to hear from a number of non-executive board members on the pressing challenges facing public boards. The theme of the forum addressed effective board governance during times of public scrutiny and how trust might be rebuilt. Board cultures have been slow to change on numerous fronts; nevertheless, the entry of the Chief Risk Officer seems to have been embraced by many boards.

It would be an understatement to say that the role of risk managers has increased in prominence since the global financial crisis. The identity of the risk manager has been codified by the Chief Risk Officer (CRO). CROs have become inextricably associated with the health of the financial sector and are seen as champions for preventing future financial crises. Increasingly, CROs are also gaining prominence in the boardroom.

How similar do today’s CROs look in comparison to those of days past? The formalisation of the CRO role started with regulations such as the Basel Accord and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Greater structural reform has been further mandated by Dodd-Frank which requires a separate risk committee for publically traded banks with $10 billion or more in assets and some nonbank financial companies. This formalisation of the CRO role has helped change their profile.

Board members acknowledge that risk managers must become more integrated into a firm’s strategy and operations in order to enable the business. However, the majority of CROs we have interviewed suggest that the integration of risk analysis and strategic thinking has not gone far enough, and that risk and strategy groups largely operate independently. During a session at the 2015 Aspen Critical Issues and Risk Forum, Harlan Loeb, Global Practice Chair at Edelman, stated that “today, the province of the risk committee is in reality small but their influence has the potential to revolutionise the leadership’s approach to risk management.”

The influence of CROs has changed and will continue to change from their quant-heavy predecessors and it is doubtful that the role will become less influential going forward. While it may seem that we are currently in a milder state in terms of financial crises, according to interviews conducted with CROs who are part of the Cambridge CRO network, the purview and responsibilities of CROs have increased in scope. Previously, the scope of CROs’ worries was dominated by credit and market risks. This scope has now increased significantly to include the full spectrum of operational risks. This includes exposures arising from regulation, cyber-security hacks, events which damage a company’s reputation, financial crime and criminal activities, and anything else that may result in overall losses for the firm.

This broadening of the CROs’ role has been supported by the regulatory community. The idea that financial systems do not necessarily work independently of society is evident in the evolution of the regulator’s stress tests. Stress tests have grown in scope to include external risks to the markets such as cyber-security threats. In emerging markets, for example, environmental concerns feature highly in the purview of stress test regimes. The Bank of England Prudential Regulatory Authority’s recently released guidance on insurers’ stress tests overshadows traditional economic shock scenarios with natural and sociological scenarios.

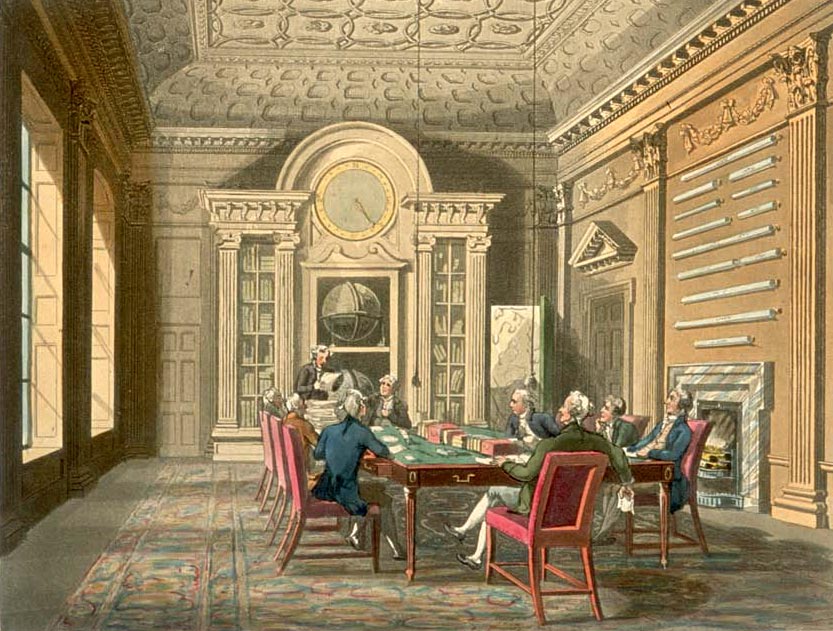

Financial institutions and regulators have been struggling to reinstate institutional trust and maintain confidence. This has also been a priority for company boards; however, challenges remain in transforming organisation and risk cultures. Professor Daniel Diermeier, Dean of the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago, emphasizes the symbiosis of diversity of counsel versus the unity in command in the board room. “Oftentimes, board pathologies comprise of a culture of no, a yes-man culture, or a culture of maybe. Constructive candour in the boardroom can help overcome these common pathologies.”

Regardless of the formalisation of their roles, CROs must continue providing value to the organisation. A CRO’s value is not always so clear cut as it may be for a role with profit and loss responsibilities since the CRO is oftentimes part of a cross-functional organisation with dotted-line reporting structures. One global bank has stated that their risk and compliance departments comprise up to 10% of their workforce.

The current skills needed from risk managers have always been essential; however, the need to exercise them was not always as critical as it is today. Risk managers still require solid quantitative skills but now they also need to be able to convey a compelling story around risk. When interviewing CROs who were active during the financial crisis, we have frequently heard that their messages were ignored in the run up to the financial crisis. Today, we are seeing a greater demand for story-telling elements as part of our bespoke training for aspiring CROs.

Boards expect the risk function to be able to balance the ability to enable and protect the course of business. Greater emphasis is being placed on the use of risk frameworks and scenarios in order to consider risks in a more holistic manner and to model their impacts within a business. For many organisations, this approach is a new contextualisation for their risk models and requires a new set of skills, different than those demanded in the past.

There appears to be a growing homogeneity in the risk organisation’s reporting structures of large firms. Previously, reporting structures were highly mixed, characterised by allegiances to the CEO, CFO, COO, or directly to the business lines, but with very few to the board. The job of the CRO has gone through a step change since the global financial crisis versus a slow evolution. Firms appear to be aware of this and struggle to adapt their internal processes such as human resources practices in order to address this need.

There have been some good studies, but given the limited time horizon and data, it is probably too early to comment on the relationship between the prominence of the CRO, firm structures and performance. However, the priorities for company boards remain focused on integrating risk analysis into both strategic thinking and operations, empowering their risk management functions in balancing risk against profit to enable their business and ultimately, rebuilding trust between broad society and financial services institutions.

Disclaimer: This column reflects my personal views and not necessarily those of the Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School.

Leave a Reply