The advances in internet communication have allowed for thoughts and ideas to flow from one continent to the next, pushing education, medicine, and new discoveries further and faster than ever before. In an ideal world, this platform would be used for good, the data would be truthful, and its motives for dissemination could be trusted. Recent events have demonstrated just how much we take this presumption for granted, as well the dangers that lie in doing so. The requirement of trust in information is essential to the longevity of democracies, where the veracity of the system depends on the availability of the most transparent data available to the voting public for their own interpretation. When adversaries seek to destroy our trust in the democratic process, is an election free of cyber interference still possible in 2019?

The road to the United Kingdom’s next General Election, held tomorrow, began with two major cyber attacks on the Labour Party’s digital platforms. Both incidents were understood to be distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, with no risk to party members’ private data. A statement from Labour assured that the attacks had failed due to ‘robust’ security systems. A subsequent unsuccessful attack on the Conservative Party was reported later the same week. Further information on the nature of these attacks may become available over time, but the implications of the attempts was clear: cyber crime has become an obstacle to fair elections in the UK, just as it has elsewhere.

Cyber interference can enter the election process through many channels. The first of these is by targeting voting demographics. “Fake news” or the spread of disinformation has become a systemic problem. False information spread through social media and traditional news outlets has become harder to identify. In a recent experiment, the organisation MindEdge found that while young professionals have high confidence in their online critical thinking skills, their ability to detect false information online is declining.

Many social media platforms, including Facebook and Twitter, are now being held accountable for content posted by their users. On 17 October 2019, Twitter released an archive of over 10 million tweets posted by accounts from 2013 through 2018. In this five year span, evidence was found that over 9 million tweets were attributable to 3,800 accounts affiliated with the Internet Research Agency with another million plus tweets attributable to 770 accounts, originating from Iran. One such account, @wokeLuisa, claiming to be owned by a political science college student in New York, became a prolific force in the #BlackLivesMatter community on Twitter. The user amassed thousands of followers and was quoted on several major media outlet including the BBC, Time, and Wired, among others. A recent study titled “Hacking Democracy” found evidence for cyber interference via disinformation campaigns for elections held in North Macedonia, United States, France, Malta, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Taiwan, Israel, and the Ukraine since 2016.

These accounts have not only spread fake news about events and candidates in during the electoral process but have become intrinsically influential to the second component of cyber interference in elections: voter turnout. Social media campaigns have been effective in reducing the turnout of targeted voter groups, promoting boycotts of the vote or targeted a particular demographic with misinformation designed to increase polarisation and political tensions.

The third method of cyber interference in elections is perhaps the most obvious, as well as the most insidious: manipulation of the election’s physical infrastructure itself. After investigations into the 2016 US Presidential Election, the Senate Intelligence Committee concluded that election systems in all 50 states had been targeted by Russia although no evidence was found to suggest that results had been altered. A case of polling interference was discovered in 2014 in Ukraine. Forty minutes before election results were to go live, a team of government cyber experts removed a virus from Central Election Commission computers that would have portrayed ultra-nationalist Right Sector party leader Dmytro Yarosh as the winner with 37% percent of the vote, compared to the 1% he received. Voter registration polls have also been targets of malware attacks, with evidence for such events found in Colombia, Indonesia, and 21 US states.

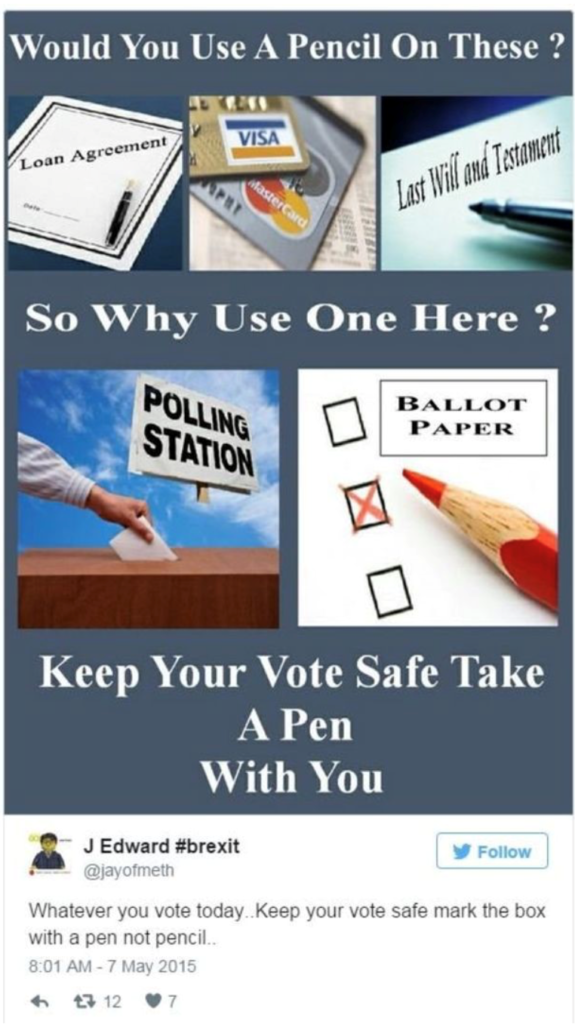

All of these tactics of cyber interference of election are working toward the same goal – to erode trust in institutions and the democratic process. During the 2016 EU membership referendum in the UK, an online campaign urged voters to use pens, rather than pencils, to complete their ballot papers. This campaign didn’t tell people not to vote, nor did it explicitly say the government was changing votes, but its emphasis on the vulnerability of voter’s choices had a demonstrable effect on voter behaviour all the same. Public trust in the government ranks low in multiple developed democracies at present. The Democracy Perceptions Index 2018 found that 64% of the public in ‘free’ countries (as defined by Freedom House) reported that their government ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ acts in their interest.

Democratic political parties in the United States and the United Kingdom have both been the targets of recent cyber interference campaigns. With impending elections in both countries, it is essential for voters to be aware the implications of cyber interference.

Just this week, UK voters encountered the deliberate chaos and distrust even a poorly executive misinformation campaign can cause. The circulation of a photograph of a four-year-old boy with suspected pneumonia sleeping on the floor of a hospital due to a lack of beds galvanised all sides of the political maelstrom. Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust acknowledged the picture’s authenticity and apologised for the lack of beds, but not before several prominent journalists and politicians fell prey to a concerted effort by bots and hackers posing as concerned, informed nurses on social media to convince them that the photograph had been staged. A recent Newsnight investigation found that the owner of the first account to post that the photograph had been staged had recently accepted a mysterious friend request on Facebook, and alleges she had no knowledge of the post when it was first made public.

The UK’s election is the first to take place during the winter – the season when the NHS’ patient load is statistically far higher and resources are stretched statistically thinner – since 1974. The image of a child sleeping on a hospital floor, while shocking, is not without the boundaries of belief for a healthcare system that is well reported as strapped for support while operating at high submission rates. This latest misinformation campaign did not realistically serve to accuse the NHS or dubious healthcare workers of feigning distress or overwork, in order to diminish political attention paid to it. Instead, this incident highlights the use of fake news in swaying members of the media to accept it as plausible fact, and sow further distrust in major state institutions who cannot seem to even get their stories straight.

Democracies are founded on the ideal that the power of representation is vested with its citizens. It is has now become the responsibility of each eligible voter to understand the external and potentially adversarial forces influencing their vote. Following the cyber exploitation of major industrial systems and data pools, companies are consistently encouraged to improve the cyber hygiene of their employees and independent contractors, understanding that their computer security is only as strong as its weakest user. Democracies now suffer the same fate, with far less ability to school their constituents and voting public on recognising undue influence. In the wake of tomorrow’s election result, there will likely be more stories from polling groups as to how fake news campaigns influenced the outcome, but few workable solutions as to how to slow cyber’s invasion of elections around the world.

RM

Fake news on social media or on various news resources can cause significant financial damage to firms as well. In today ‘s world, the reputational risk of firms is under constant threat.