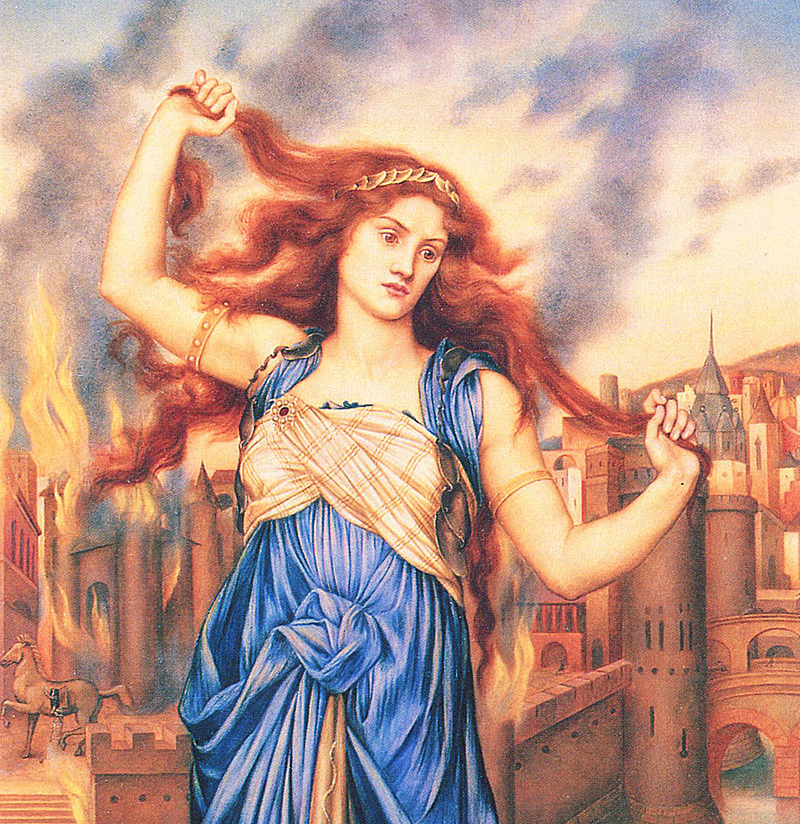

Cassandra, the mythological Trojan, was given the power of prophecy but cursed with never being believed. Modern forecasters generally suffer from the Cassandra predicament. Yet the appetite for prophecy has only expanded. As we enter the new year, it is as appealing now as it ever was to attempt to forecast how a variety of events will unfold in the course of the coming year.

The gift of reliable foresight is a power that has been coveted by many cultures across the span of human history, and everything from dreams to tea leaves and the flights of birds has been picked over and scrutinised for some divination into the events of the future. In their place today, we have institutional providers: news outlets, niche forecasters specialising in economic indicators and energy demand, for instance, and long range weather predictions. Their reports are scrutinised as were the prophecies of old. Requisite entities check scorecards of past predictions and attempt to identify which organisations hit the bull’s-eye and which ones will brush away their erroneous forecasts.

We have to ask the question: what do people actually do with the forecasts? Do they take action and incorporate them into their business planning? Early American farmers may have lived and died by the weather forecasts of the Old Farmer’s Almanac and used it to inform their investment strategies for capital and land resource planning. It is unclear whether today’s institutions are making similar bets based on external forecasts and confessing to their real utility.

The Global Risk Report 2016, just published by the World Economic Forum (WEF) ahead of its annual meeting in Davos, continues to receive attention from the business world and reaches a level of credibility in a crowded arena of forecasting. The report features the results of a perception survey of 750 members of the WEF’s global community and helps convey shared perceptions of the most pressing global risks. Davos is attended by a great concentration of CEOs and senior decision makers from the world’s largest organisations, and the WEF’s outlook for the year generates industry discourse in the public eye and receives considerable visibility.

For the past three years, the report has ranked cyber attacks among its top risks from both likelihood and impact perspectives. Particularly in North America, cyber attacks rank as the most likely risk with extreme weather events as a distant second. Cyber attacks on businesses will continue with data breach, denial of service, cloud provider compromise and extortion being major concerns for IT departments. Businesses will require greater resilience measures such as specialised cyber insurance policies to cover the risks.

It is worrying to imagine the potential scale and scope of future cyber conflicts. Unlike a natural catastrophe, cyber attacks have few natural boundaries to ring-fence their effects. They could span from minor annoyances to major economic and civil disturbances.

Solving how the world will increase its resilience to cyber-security threats is a daunting task, given the fragmented systems of governance in the virtual realm. This is particularly evident when evaluating vulnerabilities in a nation’s critical infrastructure. The public will look to government for leadership and solutions when systems are threatened or compromised, despite the fact that critical infrastructure utilities are privately owned. The realisation that modern warfare already contains a significant cyber element, which will only increase in the future, also challenges our general development of strategic doctrines for managing conflicts.

With a limited history of cyber-security attacks, it will be challenging for individual organisations to justify investments using traditional measurements for return on investment. Nevertheless, it may be timely to reconsider Cassandra and pay attention to the forecasters.

Leave a Reply